Today is the climax of the Bun Festival, the annual blend of carnival and exorcism rituals, which marks the birthday of the island’s leading god, Pak Tei (“Northern King”). At the festival site, in front of the Pak Tei temple, stalls are set out with the paraphernalia of Chinese religious ceremonies.

It is Thursday morning – in May 1989 – on Cheung Chau, the most populous of Hong Kong’s outlying islands. Though it is only 8am, the day is already hot and humid, more like mid-summer than early May: a typhoon is brewing over the South China Sea.

Today is the climax of the Bun Festival, the annual blend of carnival and exorcism rituals, which marks the birthday of the island’s leading god, Pak Tei (“Northern King”). At the festival site, in front of the Pak Tei temple, stalls are set out with the paraphernalia of Chinese religious ceremonies. A few early photographers mill around, testing photo opportunities but mainly saving film until later in the day.

Elderly women head for one of the rudely constructed, temporary buildings that have taken over a playground used for basketball for most of the year. Here, a shelter made from logs and bamboo poles, lashed together with nylon twine and protected from rain by flimsy aluminium sheets, houses three giant effigies of three gods.

On the left is the menacing figure of Dai Sze Wong, god of the underworld; touching his outstretched foot is said to bring luck. To Kei Kung, the household god, is in the centre, and the red-faced Shang Shang, god of earth and mountains, stands on the right. The women burn incense in front of the gods, and solemnly offer prayers to each.

Breakfasts for ghosts

A cacophony of cymbal-clashing, drumbeats and wailing trumpet playing announces the departure of three Taoist priests from their base beside the temple. Clad in red robes, they set off towards the harbour, accompanied by the musicians and two women carrying a bamboo tray slung beneath a pole.

The women lead the way, and soon stop at a lamp post near the ferry pier. At its base is a paper altar, beside which they set out plates of simple food and cups of wine.

A priest helps to take down a bamboo lantern hanging from the lamp post; this is then burnt, together with the altar. The plates and cups are emptied and the group moves off.

They repeat this performance at other places with the bamboo lanterns, which are often hung from lamp posts. they are serving breakfasts to ghosts, at places where it is supposed there may be roving spirits who have no ancestors to attend to them. Their route takes them past restaurant tables where streetside tables are crowded with living folk eating dim sum, talking and drinking tea, and along crowded market streets. They pass almost unnoticed, as if they themselves were wraiths that barely register on the senses, despite the musicians’ efforts and the priests’ colourful garb.

After reaching a temple to the fishermen’s chief goddess, Tin Hau, they loop back towards their starting point, and finish their rites at an ancestral hall, watched by faces from the past, which stare blankly out from an array of photographs.

A bizarre ritual

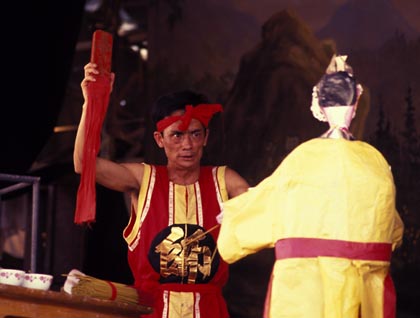

Later in the morning, another of the five priests employed for the festival performs a bizarre ritual on the stage of the festival site’s largest building, which has until now been the province of a Cantonese opera troupe. At the front of the stage, he has a table with burning candles and incense, several cups, and eggs. Nearby is an almost life-size paper figure.

The priest walks to the table, composes himself, and drains the contents of one of the cups. Then he moves to the centre of the stage, holds aloft a piece of wood, and fixes the paper figure with a stare. He then half-dances towards the figure, brandishing the wood and never relaxing his stare. Another priest shakes the figure at this advance – perhaps to signal fear – and the encounter is broken off.

The master of ceremonies then takes a live chicken and almost repeats the actions finally shaking the unfortunate creature at the quivering figure, making as if to kill it with a long knife, but then tossing it into a basket. A duck follows; then an egg is shaken in the paper face, again after the half-dancing advance that suggests the figure is an adversary to be feared.

After each mock encounter, the priest returns to the table, straightens, and stills himself, looking ahead with eyes which could be privy to the wildest hallucinations, before draining another cup and carrying on with the show.

For show it is, in part at least. A sizeable crowd has gathered to watch the goings-on and, though fascinated by the ritual, most are surely baffled as to its purpose. Perhaps it represents an encounter between priest and underworld figure, which is being persuaded to return from whence it came.

Sword-thrusting and spitting

Even the priests – whose religion nominally derives from the esoteric teaching s of Lao-Tze – are not always sure of the purpose of some rites, which stem from Taoism’s absorption of many of the traditional Chinese superstitious beliefs. Each evening during the festival, they have been performing on a smaller stage reserved for their use, changing from a text placed on an altar, and weaving their way around and across the stage.

Once the priest has done, three of his colleagues ensure that the entertainment continues by performing something similar to the nightly ritual, this time surrounded by the audience. Instead of the usual red robes, they wear an assortment of outfits, including hats with fancy ornamentation. This time, though, there is sword-thrusting and spitting – a priest takes a mouthful of tea, appears to make ready with a sword, then spits the liquid in the direction the sword points, spraying unfortunate onlookers.

During this floor show, preparations have been underway in other parts of the island for the day’s highlight for sightseers: the Bun Festival parade.

Behind the scenes

In the headquarters of the Association of Pak She district, a make-up session is in progress. With lipstick and foundation already applied, two children receive a final touch-up with eye-liner and face powder. Four other children, who have been similarly made up, wait nearby , watching or talking with parents and friends.

Both the women affecting the transformations – which make the kindergarten-age children look like small dolls – have done the association’s make-up work on Bun Festival day for several years. One is a professional beautician; the other, Mrs Cheng Wai-hing, now lives in America but returns to the island every year for the festival.

The six children will be the stars of the association’s part in the parade, and will be carried on three floats. Two of them – Lam Tsui-shan and Wong Wing-heung display outer appearances that are as different as chalk and cheese. Lam is ready with a big smile and looks set to enjoy herself, while Wong remains poker-faced, as if he considers the day deadly serious.

The time for the parade approaches, and participants from other associations head towards the assembly ground at the Pak Tei Temple. Their teams of lion dancers pause when they reach Pak She Association headquarters, to perform a dance that suggests they are offering a challenge to their rivals.

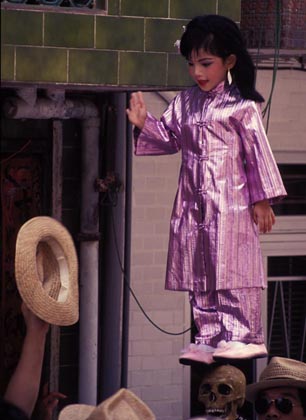

A girl is brought down from the make-up room, and five or six men hurriedly remove the wrappings from one of the floats. There are two costumes already in place on this – one high up, for a child who will appear to be held in mid-air on the most unlikely of supports, the other on the base of the float. The boy is to occupy the lower position, and is quickly manoeuvred into place and has the costume fastened around him. The float is then taken into the already crowded street.

It is Lam’s turn to be positioned. A stepladder is used to help with this: Lam is lifted up, then put into the costume above the boy, and the supports are tested to make certain she is secure. It appears that she is precariously balanced on a human skull, which is in turn on a black pyramid with the word “AIDS” painted in white, on top of a packet of cigarettes, all miraculously held aloft by the boy below, who is dressed in an immaculate white suit.

(Each float has a theme: some, such as the “AIDS” float, are topical while others are more traditional, with chilcrenn dressed in elaborate Chinese costumes.)

“This is ridiculous!” – and the float moves off

The other four children are now also in position, and the street becomes even more packed as photographers jostle for positions for taking pictures of the floats and the rather stunned-looking children. “This is ridiculous!” announces one, as onlookers try to make way for a passing lion dance team, crushing sweating bodies even closer together in the hot, claustrophobic air of the narrow street. Attempts are made to keep some space around the floats, and cool the children by wafting large bamboo fans.

The other four children are now also in position, and the street becomes even more packed as photographers jostle for positions for taking pictures of the floats and the rather stunned-looking children. “This is ridiculous!” announces one, as onlookers try to make way for a passing lion dance team, crushing sweating bodies even closer together in the hot, claustrophobic air of the narrow street. Attempts are made to keep some space around the floats, and cool the children by wafting large bamboo fans.

A signal is given for the Pak She float to move off. Flag-bearing children head the procession, then come the floats and the lion dance team – lion to the front, the musicians taking up the rear.

Crowds line the route, pressed tightly against barriers crammed into shop-fronts, or in the relative comfort of the grandstand at the Tin Hau Temple, where each of the eight associations has the chance to show off its floats and lion dancers.

When the parade halts, umbrellas fixed on long poles are held over the higher children on the floats to shield them from the sun. But they hardly seem to be in enviable positions, with movements restricted by the frames on the floats, and the elaborate costumes which – though they impress onlookers – don’t seem the most comfortable attire.

Ye, with the two-hour parade at an end, six-year-old Lam Tsui-shan says she was “very happy and very excited throughout.” She had watched the festival events last year, but this was the first time she had been in the parade and – providing she fits the weight requirements (40-50 pounds) – she hopes to be in again the next year, and maybe the year after that. The other children in the Pak She floats also enjoyed the day – even poker-faced Wong.

Bring on the ghosts

Most of the crowd disperses – the evening ferries back to Hong Kong will be full – though a few stay to watch a team of men from one of the associations dash through the streets to the Pak Tei Temple, to wave an enormous flag and perform a final lion dance.

The festival site is now almost abandoned by day-trippers, left to the island folk, the priests and the ghosts.

Events shift to a cul-de-sac leading away from the site, between new blocks of flats and the overground ground in front of a buildings which look like an old temple. By sunset, the effigy of Dai Sze Wong has been placed at one end of the dead-straight road. Beside him are smaller figures: officials in the underworld.

At the other end of the road, there is a small bamboo shelter, with table and chairs; two hands fashioned from dough are at the front of this table, their fingers folded down in symbolic gestures, palms towards Dai Sze Wong.

Between the shelter and the god, there are piles of food, drink and bank notes along the sides of the road. Beside each there is a bamboo lantern, identical to those that marked the places where the ghosts were fed this morning. People are busily adding to these piles, putting down rice and noodles, and more bank notes (drawn on the Bank of Hell).

Like this morning, the offerings are being made to the ghosts that have no living relatives to care for them, and which could cause trouble were they to remain hungry or without money.

The Exorcists

The Bun Festival is largely centred on these lost spirits, and is a rather grand version of the Tai Ping (“Great Peace”) ceremonies held in villages in south China, which are aimed at purging evil influences from the community.

Accounts of the festival’s origins differ. Some tales assert it was to placate the ghosts of people who died in plagues that affected Cheung Chau late last century; others say it was for the many islanders killed by the infamous pirate, Cheung Po-tsai, who made islands including Cheung Chau his base.

The priests are employed to ensure that the exorcism is properly carried out. By 11pm, three of them are seated in the shelter, preparing for the ghosts’ departure. A hurricane lamp allows one – the wild-eyed character who earlier did battle with the paper figure – to read fro a text placed on the table. He chants, accompanied by musicians who quietly play cymbals and drum, and occasionally increase the tempo when he indicates that the text demands it.

A crowd has gathered, mainly to wait for 11.30pm, when the ghosts will return to the underworld. They stand behind fences erected along he road, with police ensuring the road remains free.

The appointed time arrives.

The chief priest looks through an amber monocle to check that the ghosts have had their fill, and signals that they have. Men rush to Dai Sze Wong, pick him up, and throw him down on the road, where he is set on fire. This symbolises his return to the underworld; he is beaten three times to make sure he takes the ghosts with him.

Tear down the buns!

The crowd moves back to the festival site. Here, three towers standing over 12 metres high are covered with the buns from which the festival takes its name. With the ghosts gone, the buns can be given to the living. First, though, they must be brought down from the towers.

In the past, there was a mad scramble for the buns; it was believed that the higher the buns, the more luck they could bring, and battles used to break out between rival gangs racing to the top of the towers. Because of these battles, and accidents such as the collapse of a tower in 1978, injuring 24 people, these scrambles are no longer allowed.

Instead, around 10 men climb the scaffolding around the towers and await midnight, when the buns can be removed. Then, using boat hooks, the hack furiously at the buns, which tumble down onto the ground. Although the buns have been exposed to the elements for three days, and now suffer this final mistreatment, they are said to bring luck to anyone eating them. A queue of people will form early in the morning, when the buns will be given out on a first come, first served basis.

Old beliefs, and the changing festival

Elderly women arrive at a makeshift shrine beside the stage used by the priests, with roast suckling pigs and other offerings. Some throw small coins, and bend down to peer closely in the gloom to discover the results, which will indicate whether benevolent gods will reside in their households during the coming year.

Belief in old religious practices such as this appears to be on the decline, leading to changes in the Bun Festival, which dates back over 100 years. It was the tradition that the islanders become vegetarian for three days during the festival (the only flesh permitted being oysters, since oysters are not believed to have souls); eating meat and fish being acceptable again only after the bun towers had been raided. But last year, restaurants were selling their normal fare as soon as the parade ended.

The festival has shown an increasing tendency to be held for effect; it has become an excellent tourist attraction, with the priests’ ritual becoming progressively less understood. Yet it is fascinating, and good fun – especially for the children lucky enough to ride on the floats. They may have appeared rather overwhelmed by the whole business, but if all were as happy and excited as Lam Tsui-shan, they may all be hoping they do not outgrow the weight requirement and can be in the parade next year as well.